Rabiul Alam, Lakshmipur

- No children from the Manta community have ever attended formal schools.

- The lives of children in this community are confined to the deck of a boat from birth to death.

- Dreams of erosion-hit mainland children have also been washed away, leading to the dropout of thousands from school.

- Civil society members demand official categorization of the Manta community as a marginalized group.

Aroti Bibi has been fishing on the Meghna River in Kamal Nagar Upazila of Lakshmipur since her birth some 65 years ago, on the deck of a boat owned by her father. Married at an early age (12) to Musarraf Hossain, she inherited one boat after her parents’ death on the deck of the boat while fishing.

She and all of her seven siblings were born, got married, and grew up with their next generation on a boat; nobody in her parents’ family ever thought of going to school. All they practiced their whole lives was how to catch more fish.

Bibi doesn’t own a single piece of land. She has three children: Ibrahim (12), Ruhul Amin (10), and Nurun Nahar (6); and they also never went to school like their ancestors.

Aroti Bibi said, “I’m landless; I don’t have anything except this boat. I never saw anybody of my past generation ever had the opportunity to go to school as there were no such facilities for our education. The same fate happened to my next generation as well. This boat is like paradise to me, and I know I will die on the deck of my paradise.”

Enlisted as citizens, Bibi accused she has never been treated like a citizen of the country. Her family depends only on fishing for their livelihood, and they never received any aid from the government as they are not residents of the mainland and have no direct connection with concerned authorities.

This story is similar to that of all the fishermen and fisherwomen of the Manta community in Lakshmipur district.

The grief-stricken family of Sharifa Khatun, 55, wholeheartedly felt the necessity of government aid when her husband suddenly died on a boat, leaving her seven children behind. Sharifa was found struggling stridently against the river’s bone-chilling breeze to feed all her children. Nobody came forward to aid her during her bereavement period, while at the same time the government’s ban on fishing was going on.

“I found nobody, including the government, in the course of my unceasing fight against Meghna. When there is no guarantee of having a meal, education becomes just an ambition for me and my children,” Sharifa said.

Besides Aroti and Sharifa, there are nearly five thousand children in around 900 boats, mostly run by fisherwomen in charge, stationed at Matir Hat, Matabbar Hat, Battir Khal, and Ludua fish ghats in Kamal Nagar upazila of Lakshmipur district.

According to several elderly fishermen and officials of the Upazila Fisheries Department, the community is called the “Manta” community. The government has yet to recognize them as an outlying and underprivileged community like others. Although once their ancestors were on the mainland, due to consistent river erosion, they lost their homes to the riverbed and took up this profession permanently.

Their successors, even those who are earning good money by fishing, don’t feel interested in buying land on the mainland. This community does not consist of people from only one district but from some other districts as well.

Ismail Hossain, 75, a fisherman and father of four daughters, was born in Barishal district. He later moved to Lakshmipur district, where there was a possibility of catching more fish.

“Everybody in this community only dreams about buying more boats, not educating their children. They don’t know much about what’s happening on the mainland,” Ismail said.

“We don’t have any leader, and that’s why we are not getting any benefits from the government for us and our children. We also want our next generations to be educated. We demand recognition as an underprivileged community.”

However, the government under the Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) program provides food assistance to registered fishermen, as fishermen don’t have other sources of income during the fishing ban. Each fisherman gets 56 kg of rice for sixty days and 40 kg for 30 days during that period. But those who have the fisherman’s card mostly live on the mainland. Even many of the people do not have a government issued national ID card and Birth registration card that is why they do not get government aid at the same time cannot get their children enrolled in formal education as admission in primary or secondary schools require these documents of their parents and themselves.

Manta Bulbul Hossain, 30, alleges that nobody from the Manta community gets a fisherman’s card. Even businessmen from well-to-do families who have never fished or even gone near the river bank have received fisherman cards. “With no food assistance from the government, we, the actual fishermen, are having a hard time with our children in congested boat,” Bulbul added.

Bulbul further said that due to the lack of necessary support, all five of his children are limited to fishing as their only skill. Nevertheless, he harbors a strong desire for his youngest daughter, Nurun Nahar (5), to receive an education. His sentiments brought a smile to her face as she stood at the end of her family boat.

However, Saifullah, chairman of the Char Kalkini Union, which comprises some of the fish ghats mentioned above, denied those allegations that nobody from the community got a fisherman’s card. He said that the government gave him only allocations for fishermen who live only in his union.

“If someone is from another district or union, how would I give them a card defying government policy?” asked Saifullah.

Being deprived of government assistance, they take loans from local fish market owners, showing their children and boat, and are bound to sell fish only the owner’s fish box in the market, giving extra commission, including a tip sometimes.

Siddique, owner of the Hazi Roshid fish box in Matirhat Fish Ghat, said, “The loan ranges from BDT 10,000 to 10,00,000. I have also had fishermen with big boats have borrowed BDT 10 lakh from my box.”

Thus the people of this community very-often face systematic exploitation. Social activists also demanded the Manta community be recognized as an underprivileged one that should be given government funds focusing on it. Abdus Satter Palwan, spokesperson of Kamal Nagar Bacao Monch, a platform working for the rights of erosion-hit people, said that if they are officially categorized, it would be easier to get government funds only for the community.

Rasheda K Choudhury, Co-Founder of the Global Campaign for Education (GCE), emphasized that all children, irrespective of their race or social status, are entitled to receive an education. In the context of these children, special steps should be taken to reintegrate those who dropped out of school due to erosion and to address the educational needs of Manta community children.

However, denying the allegations of Manta community people, Lakshmipur district Deputy Commissioner (DC), Anowar Hossain Akanda, said that though special funds have not been allocated focusing only on the community, like other vulnerable citizens, they have also been brought under other government schemes.

“We provided homes to 50 families of the community under the PM’s Ashrayan project and built a school for the education of their children. We tried to keep all of them in one place, but they only wanted to stay by the river,” he added.

What happened to the children whose families not became a part of the Manta community after Meghna River washed away their homes?

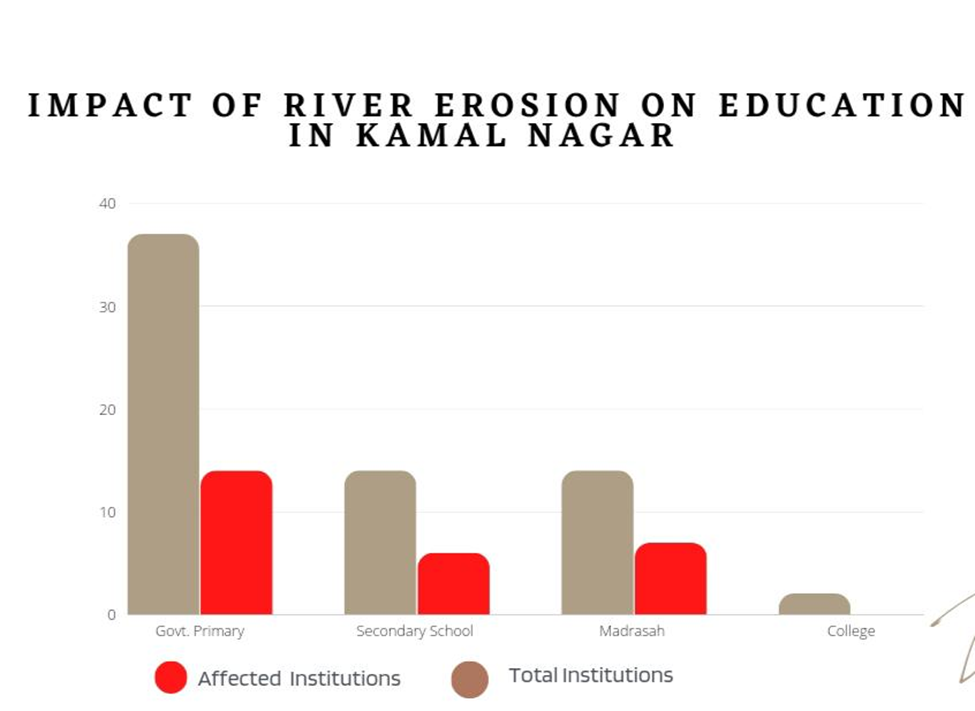

- 27 out of 66 educational institutions in the upazila have gone into the riverbed.

- No adequate initiatives have been taken to bring affected students back to school.

- Affected schools are witnessing a significant decline in enrollment.

- The upazila doesn’t have any data on affected students and their current educational status.

Not only the children of the Manta community, but also those staying on the mainland after Meghna river erosion in Kamal Nagar Upazila of Lakshmipur, are struggling to ensure education for their children. Though the children have birth registration cards to get enrolled in schools but economic conditions and the unavailability of suitable schools are depriving them of education as well. As a result, these children are joining in child labor, starting a journey towards a darker future.

Akber Hossain, 17, now helps his father, Hadis Majhi, in running their only tea stall in the Badamtali area of Kamal Nagar upazila under Lakshmipur. Akber, along with his parents and six siblings, moved to the area in 2014 after the mighty Meghna river devoured his homeland and the two-storied Maddha Char Jagabondhu Primary School, where he was enrolled in class 2, in Char Jagabondhu village under the same upazila.

Losing homeland and school to the riverbed changed everything for Akber. The new home his family built in an outlying area is more than 20 km away from his school, which is also displaced to another place nearby the river.

Akber said, “After our displacement here, I never went to my school on the riverbank, not even for the cancellation of my admission there. It’s not possible to attend a school situated at such a distance. When I came here, there was no primary school nearby.”

However, there are some tin-shed schools found near the home of Akber. But these educational institutions have been built within the last two to three years, and most of them have been shifted here after becoming the worst victims of Meghna River erosion.

Akber is not the only student who has borne the brunt of the furious river. There are thousands of students whose education has been snatched away as a result of erosion.

Faruk Hossain, 16, also lost his ancestral home in Saheberhat Union due to erosion before his family shifted to Turabgonj union of the upazila back in 2015.

“My parents lost all their belongings to the river. They also didn’t give that much focus on my education. However, I always dreamed to be a doctor, but everything washed away by the erosion,” he added.

According to the data from Kamal Nagar Upazila Parishad, Meghna River erosion has been affecting the upazila for the last three decades, and nearly one-third of the upazila has already gone to the riverbed. A total of 27 government-approved educational institutions out of 66, where around 40,000 students are studying, have been washed away by the river in the last three decades. Among them, 14 are primary schools, six are secondary schools, and seven are madrasas. Only in the last decade alone, a total of 17 educational institutions were devoured by Meghna, and students in primary level are at high risk of dropping out. Out of nine unions in the upazila, seven have already been adversely affected by river erosion.

However, data from the primary education office of the upazila shows that there are a little more than 17,000 students enrolled at the education level. But there’s no data on how many students dropped out of school after the 14 primary schools were washed away.

Kamalnagar Upazila Primary Education Officer, Jahirul Islam, said that the 14 erosion-hit schools have been shifted to safe places so that academic activities are not hampered.

“Last year, the dropout rate was 2.35 in the primary level in our upazila. We advised affected students, whose families were displaced far from their schools, to get enrolled in a new school nearby their houses. But we don’t collect the details about whether they enrolled or not,” he added.

After visiting some affected schools, this reporter found these schools had lost a significant number of students after erosion hit the schools. Having been affected, these schools also see a lack of an educational environment there, losing playgrounds and turning many storied school establishments into tin-shed small classrooms.

Jashim Uddin, acting principal of Moddho Char Jagabondhu Primary School in Saheberhat Union, said that the school had a total of 495 students when it was hit by erosion in 2014. Now this school has only 55 students.

“We have witnessed a horrible decline in primary level enrollment. We have seen only 20 percent enrollment compared to pre-erosion of the school. That means we lost 80 percent of our students after erosion,” he added.

Secondary level schools and madrasahs also went through the same situation. Abul Khayer, the principal of Patwarirhat Madrasa, said, “Once we had 400 students in our institution. Since we shifted it to a new location, we have drastically lost our old students. We are not getting new students here as well. We keep educational activities stopped in some classes because there are no students enrolled in those classes.”

However, social activists demanded a uniform guideline to bring back all students to schools.

Advocate Abdus Satter Palawan, convener of Kamalnagar Bachao Monch, a platform working for the rights of erosion-hit people, said that every day, people are consistently losing their land in the river. Alongside government schools, there are roughly 30 non-government educational institutions, including the qawmi madrasa and self-funded Ibtedi madrasah and kindergarten schools swallowed by the river. Thus, the dream of ten thousand students has been torn apart.

“Authorities should keep a database of affected students and ensure their enrollment in school after their displacement from their homeland.” “Steps including a specific guideline must be taken to keep their academic activities ongoing,” he added.

Moreover, the upazila administration asked school authorities to ensure eligible children in their area are enrolled in school. But as some families have displaced themselves to another upazila or district, it’s not possible to know their whereabouts and educational status.

Suchitra Ranjan Das, Upazila Nirbahi Officer, said that it’s a bitter truth that affected schools are lacking in students, but that doesn’t mean all of their old students dropped out of school. Most of them are enrolled in other schools. However, some students fall into adverse situations when they come to school after losing everything to the riverbed.

“We don’t have sufficient employees here; we don’t even have an officer overseeing our secondary school. I joined here only a few months ago. We will think about how we could bring back the maximum number of students to schools,” Das added.

Event status

Not started